Gallbladder removal surgery (laparoscopic cholecystectomy or “Lap-choli”) procedures are a laparoscopic procedure using several small incisions to allow the surgeon to insert 2-3 different thin instruments to perform the procedure. Prior to lap-choli’s surgeons performed this as an open procedure, meaning an open surgical field and the surgeon used their their hands and scalpels instead of guided instruments.

A thin tube with a video camera is inserted into the abdomen, then the doctor inflates the abdomen with carbon dioxide to provide room for the surgery . Several, usually two, needle-like instruments (the laparoscopic scopes) are inserted.

Several different instruments are inserted to clip the gallbladder artery and bile duct and then to dissect and remove the gallbladder and stones. The entire procedure normally takes less then 1 hour.

Complications After Gallbladder Surgery

Gallbladder surgery becomes more complicated and requires more skill and expertise now that the standard is not an open procedure but using the scoped instruments, laparoscopic procedure. Because this is a common outpatient procedure, many doctors who are not properly trained do this procedure routinely and eventually their poor skills catch up to them by injuring someone, from infections to retained instruments, causing medical malpractice.

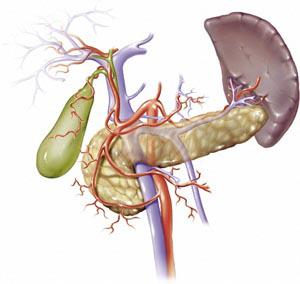

The most common negligent act in the lap-choli procedure is the doctor negligently cuts the common bile ducts mistaking it for the cystic bile duct, the duct they are supposed to cut. How does this happen? Inattention to detail and varying anatomy of different patients.

The negligent surgeons could often prevent the complications they cause by properly performing circumferential dissection around the gallbladder and clearly identifying the anatomy of the gall bladder and its adjacent ducts, arteries, and structures.

- Most Common Reason for Missouri Gallbladder Malpractice – Not Knowing the Anatomy

- Intra-operative Cholangiogram would prevent improper identification of the anatomy and thus reduce lap-choli surgical errors

- Critical View of Safety or “CVS” Explained

- “Known Risk” Defense – Cutting Common Bile Duct IS Negligent

Knowing the Proper Surgical Technique: Once the proper preparations are made for a laparascopic procedure and the surgical field is ready and CO2 is injected into the area to open up the space and allow movement of the trocars (the hollow laparascopic pole tools that allow different instruments to go into the surgical field) the surgeon should follow the general technique for the surgery:

- Elevate: Elevate the liver by grasping the liver edge with the atraumatic grasper;

- Visualize: If the gallbladder is not visualized, carefully dissect under the liver;

- Grabbing the Gallbladder: If the gallbladder is inflamed decompress the gallbladder before grabbing it; Once the fundus of the gallbladder is exposed (Fundus is the end opposite of its connection with the cystic duct) the surgeon grabs the fundus with a grasper and pushes it over the liver to the upper right of the patients body to open up the space between the liver and the colon where the bile ducts and pertinent arteries are and allows the surgeon to access the “infundibulum” which is the narrowing part of the gallbladder just before its neck and connection with the cystic duct;

- Visualize Calot’s Triangle and the Critical View of Safety: The doctor uses a second grasper on the base of the gallbladder, IMPORTANT: The direction the surgeon pulls the gallbladder at this point is very important to properly expose Calot’s triangle and the all important Critical View of Safety or “CVS”; the neck of the gallbladder should be pulled laterally while the fundus is continued to be pulled towards the right shoulder of the patient as initially described in step #4 above. POTENTIAL ERROR: If the grasper on the neck of the gallbladder is pulled anterior or upwards a “tenting” effect can occur that obscures the CVS by collapsing Calot’s Triangle which leads to increased risk for identification of the anatomy and injury to the ducts or hepatic arteries.

- Circumferential Dissection: The all important complete circumferential dissection begins by dissecting directly next to the gallbladder and taking all adhesion down to the base or neck of the gallbladder;

- Identify the Cystic Duct – Intraoperative Chloangiogram?: The doctor must accuracy identify the cystic duct and where it connects with the gallbladder, generally the “neck” of the gallbladder. Misidentification of the Cystic Duct is a Common Error in Malpractice Cases. The grasper closer to the neck of the gallbladder and opposite the fundus of the gallbladder, should be moved in all directions so that the the junction where the cystic duct the the gallbladder connect is clearly identified. IF THE CYSTIC DUCT IS NOT IDENTIFIED WITH CERTAINTY: Additional incisions can be made to manipulate the tools into a position to elevate the gallbladder and create space behind the gallbladder to open it up and make it easier to visualize the ducts. If the Cystic duct still cannot be identified WITH CERTAINTY, an intraoperative chloangiogram must be performed.

- Surgical Clips on Cystic Duct : Surgical clips (typically 2) are put as close to the gallbladder as possible and two surgical clips are also placed on the cystic duct. It is important to leave space between the second set of clips and the connection of the cystic duct and common bile duct.

- Dissect Cystic Artery Clip and Cut: The infundibular grasper (one closer to the neck of the gallbladder) is now repositioned to grasp the gallbladder as close to the cystic duct as possible. Then pull the gallbladder anterior and lateral to visualize the cystic artery. The cystic artery is dissected from the duct and the duct and artery are cut with at least 2 surgical clips left at the stump of the artery. Improper identification of the cystic duct as mentioned above also usually also leads to the surgeon mistaking the hepatic artery as the cystic artery which feeds blood to the liver.

- Dissection from Bed: With the surgical clips in place on the cystic duct and artery, the gallbladder can be manipulated further, dissected and pulled away from its bed. The dissection and pulling from the bed are completed using various tools, typically hook cautery, cautery siccors, or even a laser. Medical mistakes at this stage are rare.

- Removal: Prior to removing the gallbladder, the bed and ducts must be checked to make certain there is no bleeding or leaking. The gallbladder is then removed from the abdomen and the site is sutured. Typically, mistakes are not made at this point or after in the surgery.

The general steps above hit the high points of the surgery and the most critical portions of the surgery are identification of the proper ducts and arteries before the doctor cuts. Experience and attention to detail by a doctor avoid the needless personal injuries that occur when the wrong things are cut, not nicked, but cut. Additionally, oftentimes the surgeon does not realize that they cut the wrong duct or artery until days after the surgery when the patient presents with complications.

Our Gallbladder Surgery Complications Attorney in St. Louis Can Help You

Our St. Louis medical malpractice lawyers will review your case for free to determine if there is actionable negligence. Call us today at (314) 863-0500.

Site by Consultwebs.com: Law Firm Website Designers/Personal Injury Lawyer Marketing.

Site by Consultwebs.com: Law Firm Website Designers/Personal Injury Lawyer Marketing.